A New Beginning

In the mid-1980s a group of 18 Guatemalan tenant farmers or sharecroppers decided that they’d had enough and protested against the drudgery inflicted on them and their families. As a result they were evicted. Among them they had very little money, the average amount some Q 3,900 for 19 years of work (roughly US$ 500), and they had to live on wetlands that wouldn’t yield. Luckily (and through friends of friends and Guatemalan peasant organizations), they made contact with a Canadian charity organization which donated enough money for them to buy a piece of land that could sustain them.As was to be expected, the beginning was tough but also exciting. It turned out that the piece of land had been an ancient place for worship of Mayan gods. This the settlers found out when they tried to move a big stone situated where they wanted to build their communal “pila” (washing place). As is customary, the women had been washing their clothes in the brook that runs through the settlement, but now since they wanted to become an organized community they were trying to clear the area of boulders.

The communal pila with the sacred stone

They moved the stone, but to their surprise, the next morning the stone had rolled back to its former position, and when this had happened twice, they decided to let it rest. At the same time many people were hearing screams, sounds of dogs fighting, and titter-tat and whispering of unknown people, and it turned out that the sounds came from around another big piece of rock. This rock had fallen face down long before, and not until it was erected did the strange sounds go away. One side of the rock showed carvings (glyphs = glifos) of an owl, and once it was washed and set straight everything was quiet.

The ornamented stone

All of this was foreboded by the presence of a number of featherclad serpents who emerged when the villagers cleared the spring of the brook, a thing first discarded but now recalled. Right next to the big stones they later found an ancient altar which is now in use for Mayan ceremonies, not only for the people in the community, but for everybody else in the neighborhood.

The altar

When news of the finds spread, the archeologists moved in, and for some time it looked as if the establishment of the community would come to a standstill, but luckily, the introduction of a new law protecting the autonomy of sacred places secured the villagers’ right to carry on undisturbed. As another unexpected stroke of luck, the local mayor supported the villagers and saw to it that electricity was installed and that concrete roads were built (the city supplied the cement, the villagers the work) but there’s still no running water; their only water supply is the spring and the little brook.

The atmosphere is very pleasant and almost jungle-like

Coffee grains out to dry on the concrete streets

Although the first mayor of the nearby city helped establish the community, the following mayors did nothing of the sort, in fact, they sent in the police and the army to watch the village, accusing them of contact with the Guatemalan guerillas in the final years of civil war (the peace settlement was signed in 1996 after 36 years of unrest). The children in the village were instructed not to give names as to “Who is your leader?” (“We are all leaders”). This is still going on, and the name and location of the village are therefore withheld for exactly that reason.

Una mamita cleaning corn

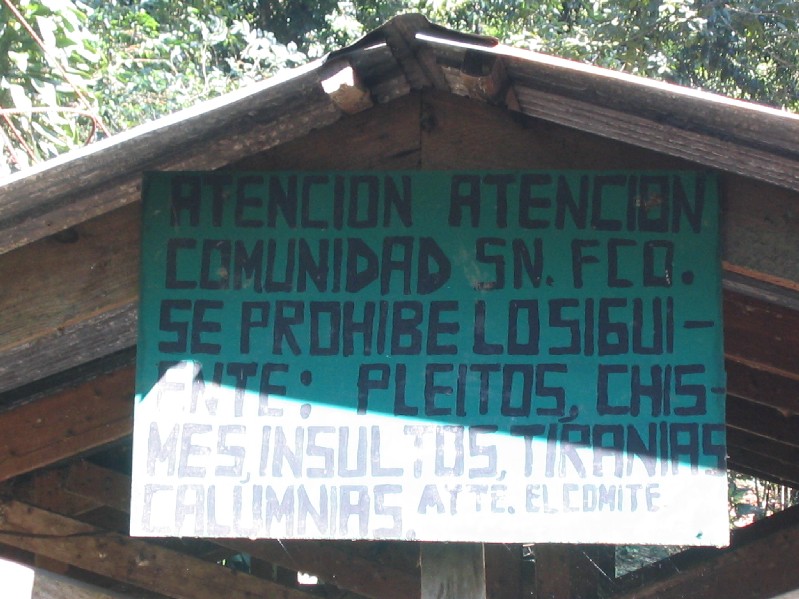

Sign says: No mockeries to be spoken here

And they do live in a kind of “Communist” harmony that dictates that everyone works his share and shares the profit alike. This may only work in a small community with a history like this one, but the present success is a strong pointer to ways to overcome obstacles when trying to establish new societies. Most probably, some Mayan respect for a community feeling needs to be present to accept the sharing, but the village certainly qualifies.

But there’s still no teacher (they have a room to set up school), and until then there seem to be limitations as to a proper integration into the Guatemalan society. Besides, many of the men have to seek work outside the village to earn more money, but due to the surveillance, which means that they are seen as potential troublemakers and therefore not welcome labor in the nearby communities and farms, they have to travel far to get work. They have tried to breed fingerlings, and hogs, but both projects failed - the spirits wouldn’t let them, the Mayans say. Still, there are so many positive vibrations to be felt in this Mayan community that one can only hope that the village will survive and the news will spread that it is possible to establish a new and different beginning.

Laundry out to dry on the corrugated rooftops

Erik Moldrup

November 2007